The Foreigner Question - Yasmin Gunaratnam

/Image http://andreasmoser.wordpress.com/

'Health tourists', migrants as a 'drain on resources' and that 'racist van'. July was a busy month if you were trying to keep up with Government strategies for tighter controls on immigration and welfare spending.

The announcement of proposals to curb health tourism caught my attention. I am spending a lot of time in hospitals and hospices these days, working on a project on transnational dying. When it comes to migrants, the problem that health care professionals are talking about is under-use, not abuse of the system. People often don't feel that they are entitled to services, a Cancer Clinical Nurse Specialist told me last week. This can lead to unnecessary suffering further down the line with advanced cancers that could have been treatable if help had been sought earlier.

The organisation Doctors of the World UK says migrant patients at their London clinic find it especially difficult to access health care. “In our experience so-called ‘health tourism’ is a myth,” says Leigh Daynes, the Executive Director. “Most patients at our clinic have no knowledge or understanding about how to get care from a GP. The majority have come to this country to work, or to seek safety from persecution for political, religious, ethnic or sexual orientation reasons, not to get medical care.”

Image: J Aaron Faar (Creative Commons)

The figures used to calculate the costs to the NHS of 'health tourists' vary according to whether you are using the the private or NHS tariff. The Government were using the latter. Data presented by the Guardian show that some £11.5 million had to be written off in 2012/13 because the NHS was unable to claim back costs from foreign nationals. This is because people were untraceable, could not pay or had died. In some cases there isn't the organisational capacity to chase the payments. In any event the £11.5 million amounts to 0.01% of the £108.9 billion NHS budget for the same period. For the Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, there is also a principle at stake in the proposed reforms 'We have been clear that we are a national health service, not an international health service".

Thinking about how costs for care and for health might be calculated and the ways in which the 'national' in the NHS is being emphasised relates to philosophical discussions about hospitality and the 'foreigner'.

The book 'Of Hospitality' by philosophers Jacques Derrida and Anne Dufourmantelle is one of the first books that I read that seemed to capture the practical and symbolic significance of being vulnerable in a strange place and of giving hospitality to a stranger. In the very first essay, Derrida hooks us in with knotty little word plays about the foreigner as a 'being-in-question... '[p.3]; a figure that provokes thinking about our own place in the world. The most basic of our responsibilities, our responsibility to others, Derrida suggests is embodied and pushed to its limits by the foreigner who needs care.

One of the most provocative and tricky ideas in the book is about hospitality as holding a tension between the unconditional welcoming of the stranger and the need for rules, conditions and regulation. For example, important distinctions would be made in the hospitality that is given to asylum seekers fleeing persecution and those who are war criminals.

Despite the dense language, the points that Derrida and

Dufourmantelle make are worth holding onto at this time. And they are not as

abstract as they might seem.

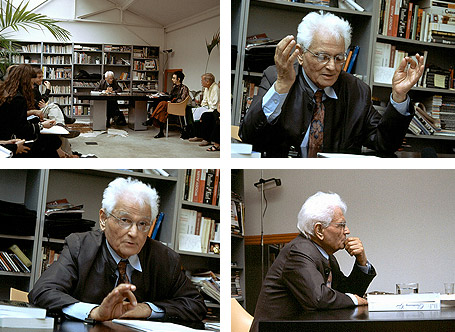

Images of Jacques Derrida by Hendriq Speck, Creative Commons

On Saturday Roseline Akhalu, a Nigerian student won her appeal against deportation from the UK. Roseline had a prestigious scholarship to study at Leeds University in 2004. Quite suddenly she suffered renal failure and received a kidney transplant in 2009. The Home Office have been trying to deport Roseline for four years. The appeal judges ruled that her deportation amounted to a death sentence since she could not afford the drugs and care that she needs in Nigeria. Others have not been so fortunate.

In January 2008, Ama Sumani, a Ghanian widow with malignant myeloma was taken by immigration officers from her hospital bed in Wales to Gatwick airport and deported. Her visa had run out and she had no legal right to remain in the UK. The prestigious medical journal The Lancet described Ama’s deportation as ‘atrocious barbarism’. There was also the chuntering of disgruntled citizen commentators in the blogosphere and on the airwaves who supported Amma’s deportation amidst fears of treatment tourism and an already over-stretched National Health Service.

Image Dave Knapik, Creative Commons

Ama died three months after her deportation. In that time over £70,000 had been raised by supporters and friends in the UK for her treatment and drugs. Speaking to the controversy and resentments surrounding Ama’s case, the BBC’s East Africa correspondent, Will Ross put forward an alternative set of moral coordinates. ‘Turn up at a British hospital and do not be too surprised if the nurse or doctor who treats you is Ghanaian. With the drain of this exodus on the Ghanaian health service, some here suggest the UK might owe Ghana a favour or two.’

Such global interdependencies in contemporary health care provide another perspective on how we might re-imagine the 'national' in our National Health Service. A recent study in the British Medical Journal found that more UK residents go abroad for treatment, than those who travel to the UK for health care. For at least four decades, some quarter to a third of all doctors working in the NHS have qualified overseas. A 2011 study of nine sub-Saharan countries found that the countries lost an equivalent of $2bn as doctors left to work overseas. The benefit to destination countries of recruiting trained doctors was largest for the United Kingdom ($2.7bn) and the United States ($846m).

Besides this indebtedness that British citizens have accrued to overseas medical expertise over recent decades, there are many other traces of `foreignness’ that have insinuated themselves into the hearts and minds, tissues and organs of the bodies we like to think of as our own. The science historian George Sarton insists that we owe the very institution of the hospital to Islamic medicine. Then there is the vast relief of pain provided by opiates – now themselves the site of another `battle for hearts and minds’ – that flowed in repeated waves from east to west over thousands of years. As Sheila Payne, Director of the International Observatory on End of Life at Lancaster University has pointed out, there are stark and complicated disparities in access to pain relief across the globe. There is little profit to be made from cheap oral morphine and legal and regulatory barriers still exist in many countries. We are a part of that privileged ten per cent on the planet who consume 90% of the world's opium supplies.

The Foreigner Question that Derrida and Dufourmantelle have articulated feels entirely real and relevant in thinking more deeply about the extents of our global connectedness and responsibilities when it comes to health. This is a complicated responsibility. It demands that we think carefully about hospitality, about what and how we give. Perhaps most subversive of all, it would also have us recognise what we receive.