Death and The Migrant - Yasmin Gunaratnam

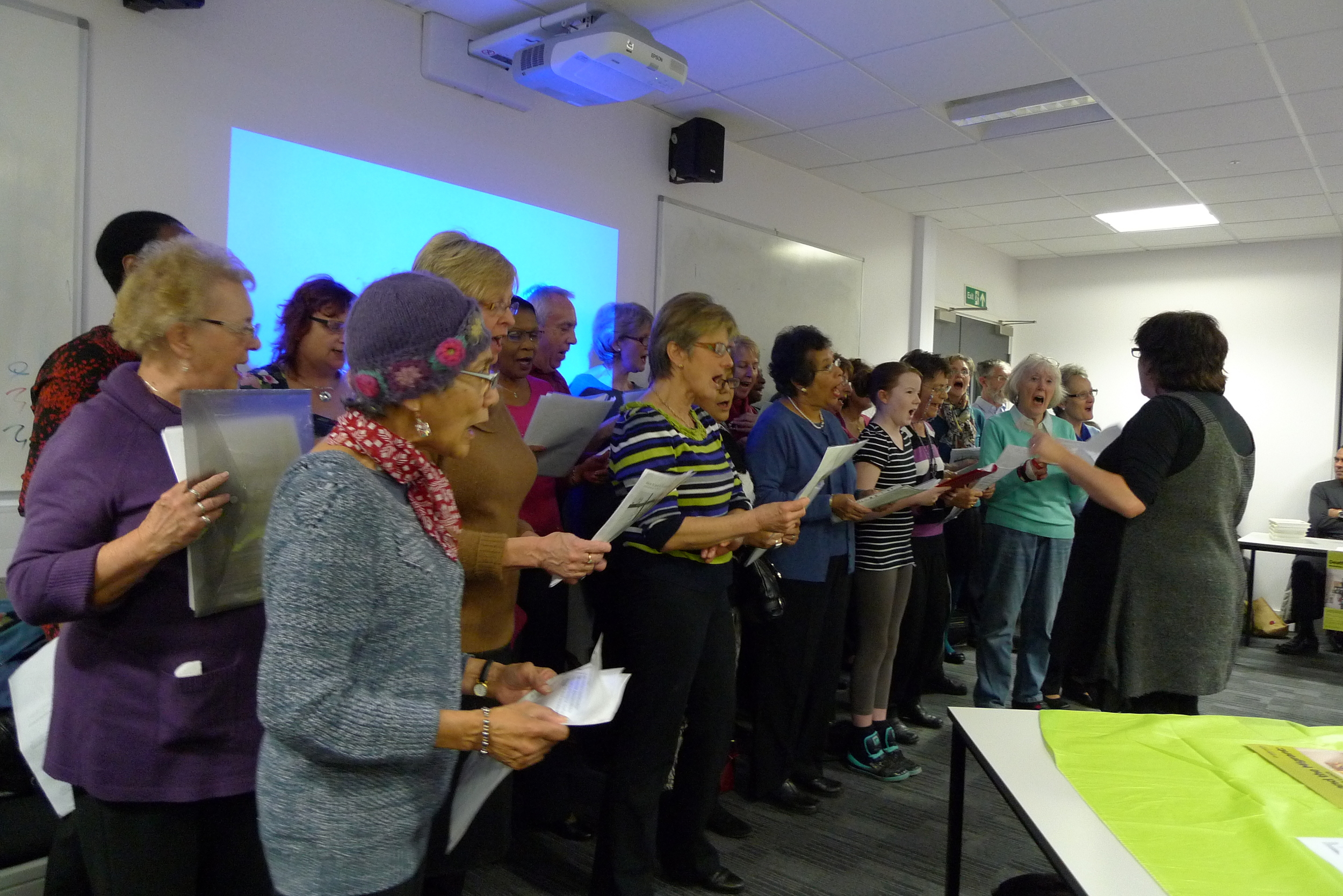

/St Christopher's Community Choir, Image Marina Silva

Last week was a big week for me and saw the publication of my book Death and the Migrant. Here is the text of my short talk that should give you a flavour of the book launch and workshop at Goldsmiths. Each of the contributors was asked to respond to themes and chapters in the book. We started with a sonorous response from St Christopher's Hospice Community Choir. The choir includes local residents, patients and those who have been bereaved. It was a rousing start to the evening.

Canapes and poems, Image Marina Silva

Apart from me, there were three other responses. Mariam Motamedi-Fraser, a writer and sociologist at Goldsmiths, talked about ‘Of words and worlds’. Gerry Prince, a musician and music therapist, took us on an acoustic journey into a care home, ‘When music is your only friend’. Using the title ‘Guest-ures’, Margareta Kern spoke about her work with migrant women and with custom and ritual. Margareta also gave us a chance to talk about what we had heard and to respond to the archival stories and poems of social pain and experiences of diasporic dying that had been left at the tables. At the end of the launch we went downstairs to see the exhibition 'Dying Creatively' of patient art curated by the arts therapy team at St Christopher's, our local hospice.

Dying Creatively Exhibition at Goldsmiths, Image Marina Silva

Image Marina Silva

Death and the Migrant

Image Marina Silva

As some of you will know, this book has been a long time in the making. It is an experiment in writing, in commemoration and in trying to account for some of the emotional and bodily costs of geo-social inequalities, war and racial hatred and the unceasing demand for cheap, healthy migrant labour. There is simply no place in global capitalism for the debilitated and dying migrant or for thinking about what the build up of injury, hurt and loss can do to a life. These losses and pain come in various forms, tempos and scales. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has talked about them as ‘large’ and ‘small’ misery, the social suffering caused by towering structures of inequality and the mundane injuries of damaged social relationships. For those such as Lauren Berlant writing about obesity and Rob Nixon charting environment hazards, there is the idea of a slow, barely visible wearing away of vulnerable populations. Forms of social pain that neuroscientists are beginning to map, adding empirical evidence to the claims of feminist and postcolonial theorists of how pain can accrue over a lifetime and can be transmitted unconsciously from one generation to another.

And as those working in health and social care know very well, in situations of illness and disease, pain makes inventive coalitions and shapes. Harshini’s mother, a devout Hindu, has dementia. She wonders out of her house in Leicestershire telling her family ‘I am going to the fields’. ‘Although she is here, in her mind she always thought that she was back home’ says Harshini, adding ‘and even today although she is not aware of what she is doing with her hands, without a mala…her fingers are still working as if she is praying.’ In Harshini’s story, we hear of some of the ways in which disease can rearrange time and place and we also hear about the tenacity of culturally honed sensorium.

As some of the other stories in the book also show hallucinations, paranoia and hypersensitivities can cohabit with and jostle among prayers, promises, plans, habits and rituals, tugging and drawing the body and self in new directions in what I think of as diasporic neurology, where there can be a scattering of sensibility not only throughout a single body but also across and into the bodies of others, moving, unsettling and endowing them in what the philosopher Ros Diprose has called ‘Corporeal Generosity’. ‘What makes me think?’ Diprose asks, ‘Something gets under my skin, something disturbs me.’

Gill, a hospice nurse caring for a Ugandan refugee dying of AIDS related conditions knows something about such affects even though she is not quite sure how to respond to these complex phenomena. Like so many of the care professionals that I have interviewed and taught over the years, Gill is haunted by the memories of those situations where care falls short. Gill tells me about caring for a Ugandan mother, dying alone in London without family or friends. The woman did not speak English and may also have had AIDS related dementia. Her silence, blank face and utter aloneness haunt Gill. What are the relationships and tonalities between cultural difference, trauma and disease? ‘I found we never really got alongside her’ Gill says, ‘I suppose I view that as a failure of care ’.

Photo Marina Silva

Haunting is a trope used by scholars of trauma to make sense of the effects of spectral and oblique social forces - of violation unrecognised. What is repressed but will not go away. ‘Haunting and the appearance of specters or ghosts is one way’ the sociologist Avery Gordon has written ‘that we are notified that what’s been concealed is very much alive and present.’

Sifting through box after box in the Cicely Saunders archive in the Strand, these ghosts appear as curious asides, anecdotes or as problems. The first direct mention of a migrant I find in 1958, but there are many more. Mrs S is described as ‘A charming West Indian; in pain; tearful and depressed. Much alone with her illness’. There is Mrs P “A patient with an extermination camp background who later developed severe depression with hallucinations, helped by E.C.T.” After an Egyptian patient come the two words ‘Another loner’.

Pain as a complex blend of the biological and cultural is a central theme in the book. Hybrid pain can be difficult to locate and to name, sometimes withdrawn from the present and from language. It lies encoded in our homes, cultural institutions and in the memories and bodies of those who care. It is misdiagnosed or unrecognised, even though the very idea of the modern hospice and the palliative care philosophy of total pain took form in the shadows of the holocaust and in Cicely Saunders’ relationship with David Tasma, a dying Jewish refugee from Warsaw, whom she met at St Thomas’ hospital in 1947. David bequeathed all of his money - £500 - to Cicely so that she could use it to help her realise their plans for a better place to care for dying people. Saunders’ vision for the first modern hospice - St Christopher’s - reads like a cultural elegy for multiculturalism: ‘A community of the unalike’.

Keeping in mind the political economy of migration that flashes up from time to time in the media porn of catastrophic events such as Lampedusa, Death and the Migrant, is an attempt to record the everyday borders, predicaments and improvisations entailed in migration over the life course. There are surprises, experiments, playfulness and dissimulation; bodies and stories that overflow, and the generosity and poetry that is good care. As the philosopher Jacques Derrida has recognised, the giving of hospitality to a dying stranger is potent in its cultural symbolism and ethics. It is also a very real occasion through which unspoken histories, losses and the extents of community and hospitality can be imagined and felt. And not least for the migrant researcher.

This has been research that is not so easily contained and finished off. I realised when I was preparing for today that I did my first work with St Christopher's in 1994. For all that it is and it isn’t, the book is also a work of mourning and circuits of loss that I am only just beginning to make sense of. I am deeply grateful to the patients and professionals who entrusted their stories to me. I have come to realise the ways in which stories take the dead across borders and boundaries. This is why we tell them.

I read Grace Cho’s disturbing and compelling book on the Korean partition and diaspora. ‘I no longer remember the details’ she writes, ‘but sometime, somewhere, something was lost, and I started to look for it.’

Talking & responding to stories of social pain, Image Marina Silva