Narrative and stories

Clinically and therapeutically, stories and narratives are integral to illness and care because they are events of meaning making that draw people into relationships. Stories can evoke the singular complexities of experience, a point recognised by D.H. Lawrence when he wrote: ‘The novel is the highest form of subtle inter-relatedness that man has discovered’ (quoted in Leavis, 1967: 11). ‘To attend to a person’s stories is to enable his or her self-discovery, and that is an act of care’ the sociologist Arthur Frank has argued (2010, p. 161).

Thinking of narrative as an event of meaning making and as involving moral relationships between the story teller and listener/witness, marks a shift away from a mimetic assumption: that narratives are a transparent reflection of a person’s experience and rational choices, a view that has been called ‘narrative fundamentalism’ (Shapiro 2011, p.68). Sometimes referred to as ‘constructivist’ or 'dialogic' – what these latter approaches share is the belief that we continually create and refine our experience, and indeed our moral agency, through the stories that we tell. Related to what has been called a ‘crisis of representation’, constructivist/dialogic perspectives recognise the potential for the meaning of stories to be multiple, as well as ambiguous, as they unfold over time.

At the end of life, the temporality of stories and their emplotment can change. 'In the terminal phase of life, looking backward constitutes much of the present', the doctor and anthroplogist, Arthur Kleinman argues, in his book 'The Illness Narratives',

'That gaze over life's difficult treks is as fundamental to this ultimate stage of the life cycle as dream making is in adolescence and young adulthood. Things remembered are tidied up, put in their proper place, rethought, and equally important, retold, in what can be regarded as a story rapidly approaching its end...Constructing a coherent account with an appropriate conclusion is a final bereavement for all that is left behind and for oneself.' (p.49-50).

Cicely Saunders, who is regarded as founding the contemporary hospice movement, collected and worked with the stories of dying people – as well as their photographs, artwork and poems – in developing her ideas about ‘total pain’ and end-of-life care. Saunders was an early, although often unrecognised, practitioner, of what is known today as ‘narrative medicine’. She believed that the ability to listen and to be receptive to the stories of dying people was vital in witnessing and receiving their pain and humanity.

What are narratives and stories?

There is much debate about what narrative and stories are. Some writers feel that defining and categorizing their respective features can lead to a distancing from the moral and emotional demands of stories (Frank 2010). Others insist that some understanding of the different qualities of a narrative and story can lead to a deeper appreciation of a patient’s unique situation and how a narrative can affect the listener. Sayantani DasGupta (2008), a physician and practitioner in the Narrative Medicine Program at Columbia University, refers to this stance of recognising how narrative and stories work upon the listener as ‘narrative humility’. In DasGutpa’s words, narrative humility enables a practitioner ‘to place herself in a position of receptivity, where she does not merely act upon others, but is in turn acted upon’ (p.981).

Drawing upon concepts and techniques in literary criticism, John Paley and Gail Eva (2005) also believe that narratives work upon those who receive them. It is because of this that we need to be attentive to how different stories affect us, they argue. Paley and Eva define a narrative as an account in which a sequence of events is causally related, with one event leading on from another. In this regard, a story is a narrative thickened. In addition to related events, a story has a plot, a character(s), a problem and an explanation.

Most importantly, a distinguishing feature of the ‘narrative machinery’ (Paley 2009) of a story is how it works to elicit an emotional response. In light of the emotionality of stories, Paley and Eva have advised ‘narrative vigilance’, warning that care practitioners can be drawn to certain stories and be persuaded by their surface meanings (as well as being repelled by others), because of their emotional resonance.

You can download John Paley's chapter on 'Narrative Machinery' from the collection that I co-edited with David Oliviere - Narrative and Stories in Healthcare - here.

Narrative Windows

The sociologist Arthur Frank has been writing about illness, the body and stories since the 1980s. In his 2010 book Letting Stories Breathe, Frank draws upon the work of the feminist theorist Donna Haraway and argues that stories are our 'companion species'. ‘Stories work with people, for people, and always stories work on people’ he writes, pointing to the ways in which stories are both relational and performative – stories are not only containers of experience, they are experience; they act and do things.

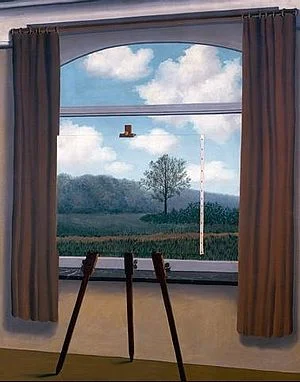

Frank offers a vivid visual metaphor for thinking about the ‘layering of imagination and realism’ in stories, using René Margritte’s painting La condition humaine,

René Magritte's The Human Condition, Source http://research.uvsc.edu/albrecht-crane/3400/human%20condition.jpg

'A painted canvas sits in front of an open window, partially blocking the view through the window. The realistic image on the canvas is perfectly mimetically continuous with the view through the window. Yet…the edge of the canvas interrupts the continuity of views…And then the viewer remembers that the whole picture is painted…If the human condition is to experience the real through its representations, those representations are not necessarily distorting. But neither are they the real itself.'

Frank’s argument is that once we have learned that stories are never transparent windows onto a reality, we can begin to attune to the storytelling relationship and to how the artist/storyteller has sketched her windows onto reality. We can also take up the offer of dialogue that stories invite.

Despite differences between approaches to illness narratives, what most authors seem to share is the belief that narrative knowledge can inform care-giving in two main ways: through the appreciation of the content and the form of what is narrated (Jones 1999) and, second in how we understand the ways in which meaning is jointly produced by the narrator and listener/reader.

Anatole Broyard has written ‘ Inside every patient there’s a poet trying to get out’ (1992, p.41). For Broyard the most responsive clinician (and we might say listener) is someone who sees beyond the most obvious signs and symptoms of illness - someone who learns to feel the intricate poetry of a story's messages.